Joining a Purgatory for Artists

My experience quarantined on an art island with no access to the outside world

I signed up for a quarantine on an abandoned, private island in the Mediterranean with renowned painters, illustrators, gallerists, and aspiring artists without phones or connection to the outside world. I wasn’t sure what to expect. The course was called Qvarantine Events; I found it online after seeing one of my favorite painters participate in it as a mentor. Its bold, alternative aesthetic instantly drew me. This wasn’t a course for abstract, conceptual art. Neither was it a nostalgic attempt to return to the past. It was a unique project to forge the figurative artists of the future. It is curated; one needs to apply through a rigorous process.

Part of its value is secrecy. You’re not allowed to mention details about what happened to allow the incognito element for future participants. Does this sound like a cult? Yes. Do the organizers care what others think? No. They’re confident in their intention.

When we set foot on the island, we were given rings, jugs, and diaries with the organization's symbol. The island is in Menorca. One might think—a mellow holiday on the beach with a canvas? Those who prepared for such an experience were met with an abrupt realization. It was intense, mystical, daunting, and challenging. Yet, at the same time, transformative. We were shaken to the core. The island has a sinister, powerful energy. It felt like Middle Earth; not coincidentally, the course is described as a “purgatory for artists.”

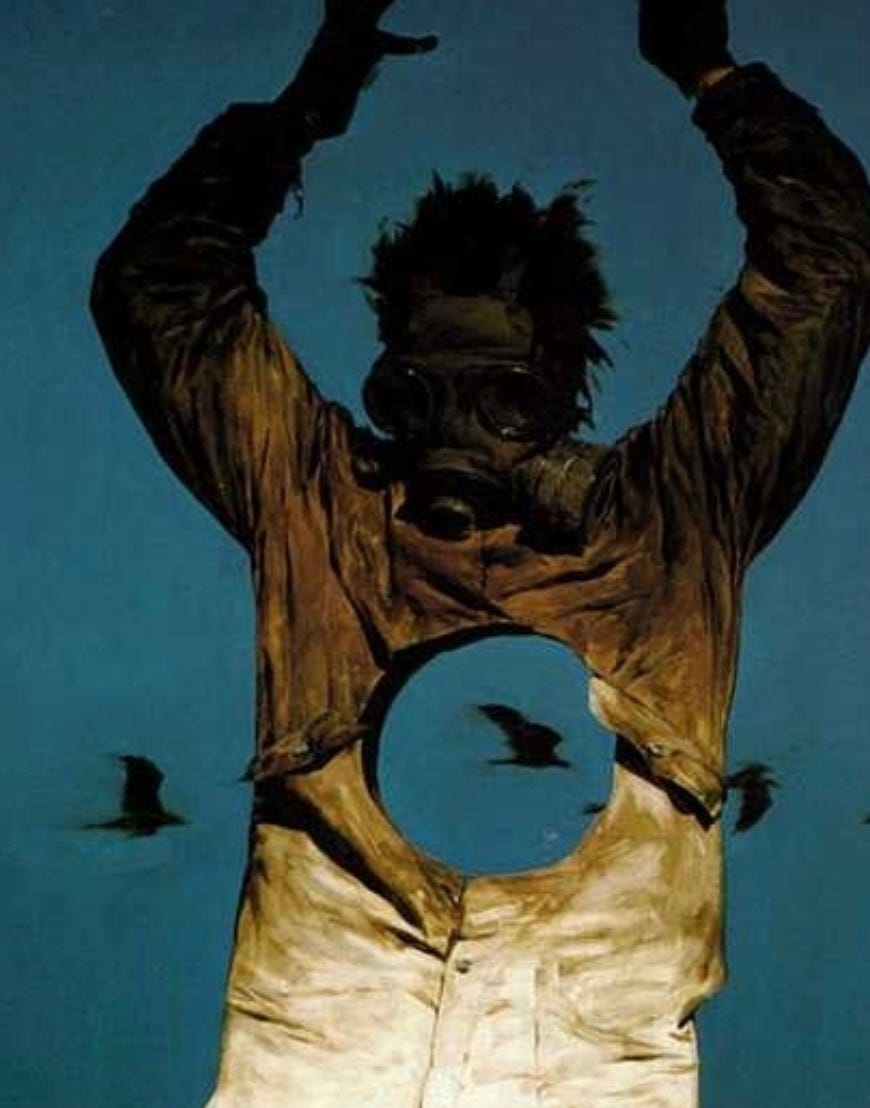

I wasn’t aware it was a literal quarantine island from the 19th century. Now abandoned as a relic, it is owned by the Spanish government and rented privately. When we arrived, the gate said “Lazareto,” inspired by the first quarantined islands created in Europe against the plague and cholera outbreaks, where the sick were sent, often never to return. It was uninhabited, composed of watchtowers, prisons, rooms, and warehouses, where the ill were strictly divided to avoid infecting one another. Criminals were often sent to the island to become servants of the sick as punishment. Now, it was free; taken over by creative artists. Nude models posed with gas masks under trees. A certain irony was obvious to many of us.

What struck me most was seeing where the inmates were once kept. One large panopticon, where a small watchtower was surrounded by circular cages, in which a priest would speak to the sick, imprisoned individuals. This was the panopticon first envisioned by Jeremy Bentham, the Enlightenment philosopher I studied at University. Later critiqued aptly by Michel Foucault as the engineer of a control system. After all, does isolating individuals help them overcome their disease? Hardly so. The energy of despair transpired through the metal barricades. I had dedicated my master’s thesis to critiquing a structure that was now staring at me. I was no longer writing about it on paper; I could feel its energy penetrate my bones.

Other cages were meant for loved ones paying their final goodbyes. Two layers of gates were built with a middle space filled with vinegar to avoid infecting the visitors. I imagined the scenes. I felt an urgency to subtract myself from them. Yet my usual distraction - my phone - was missing, as it was strictly prohibited. So, I often ventured alone on this remote island. A quiet, relaxing solitude in the autumn chills next to the sea. But then, I would need to find my peers again to fill in a sense of emptiness from the abandoned edifices.

There were about eighty of us. I almost instantly became friends with two girls from northern Italy. We formed our tribe. Something about not having phones compelled people to speak to one another. It made us reflect on the fact that this was what real life consisted of: awkward, spontaneous conversations ending in lasting connections. We weren’t taking a break from our daily lives; we were living life as it was meant to be before screens filled our sense of inadequacy—a necessary sentiment of discomfort that can lead to the most beautiful surprises.

We had incredible artists who gave us, in turn, a speech every morning: Edward Povey, Henrik Uldalen, and Phil Hale were the ones I had selected to be my private mentors. But they weren’t teaching us their method during their speeches. Their lectures were more profound. They told us their life stories, often confessing delicate, sometimes violent, personal struggles they used for their art in a place they knew was safe to talk about because it was confined. The common denominator I observed was their rage, triggered by their sensitive souls – the overwhelming emotions that can make for exceptional artists. A feeling of strength compensated by an equal, opposing sense of fragility. But that overload of energy was harnessed to create. I told myself I should do the same.

Here are some of my favorite quotes from the mentors I chose. Their paintings below:

“I always had the most exquisite love affairs; on the treadmill of fears I was longing for angels and purity of heart.” Edward Povey

“I don’t care what my children decide to study in school - I only care that they become themselves.” Phil Hale

“After the death of a person I loved, I told myself I would never suffer that way again. I succeeded. I could no longer feel anything. That is when I realised that a life without emotions is not worth living.” Henrik Uldalen

I used the diary the organization gave me to report the moments, events, and dialogues I wanted to cherish. Diaries, in my view, shouldn’t be used to document every moment of our day but to write down what is meaningful to us. To absorb the instances that teach us the most valuable lessons, to increase the reverberations of their impact.

Since I can’t spoil the experience for future visitors, I will say this much: we held intense art laboratories during the day. Sometimes, I could barely participate in them because they aimed to break our conventional wisdom. I felt provoked. I was overpowered by what they were trying to bring out in us: not a work of art - we could do that in our studios and academies at home. Their purpose was to force us, though of our own free will, to listen to our intuition—to strip away the barriers that inhibit us from fulfilling our creative potential. To not give us room to think. Somewhere in between discipline and surrender, one finds the catalyst.

As for the photo with torch flames under a full moon, and the other videos you might have seen on social media with ancient music and dances, I cannot disclose the details.

I can say that the island oscillated between the Apollonian and the Dionysian. We had strict, disciplined hours dedicated to our art followed by wild events.

Our one-on-one mentorships with the artists allowed us to develop personal connections. I won’t say which mentor said what because these were private conversations, but one of them made me cry. He said, “Your eyes make me fearful.” I laughed to lighten things - I felt embarrassed, to some degree. I didn’t want to make him feel fearful. I wanted him to trust me. He responded, “It’s not funny.” A moment of solemnity before tearing through my psyche with personal questions intended to release my most compartmentalized emotions. Another one said that I should “let loose that part of my brain that says things should be done a certain way”. I’m quite attached to outcomes, which I now understand is not always good, as it inhibits us from enjoying the process. Lastly, one of the painters told me that a girl on the course had a “better scholastic skill” than mine but that she was just a good student and that I was more of a problem. He meant it in a good way. That was the first time I was complimented for such a trait.

It felt that fate was fulfilling its course; as I became interested in the ancient Pagan faiths of my ancestors, I was thrust into an environment where I experienced their ritualistic traditions. One night at a bonfire, I spoke to a martial artist who was one of our painting models. He told me he saw a vision of Athena, the goddess of wisdom, war, and handicrafts, and became increasingly interested in Greek mythology. It was a strange coincidence, but I don’t believe coincidences exist.

I understood about humanity through this experience that cults and tribes can be our natural state. Not in a censorious way. Rather, in a way that enhances our freedom by making us feel emboldened to give life to our creativity with those who share our passion.

I now have a clear direction for my art, which I am thrilled to share with you. They accomplished their mission to unlock the artist within me, so if you’re interested, I encourage you to look into this course. My friends and I discussed how it triggered an existential crisis in us in the best way.

At the same time, the quarantine came before launching a magazine I have been working on for a while—not in art but in journalism. If you’re interested in learning more, here is the link to follow: www.alatamagazine.com and, for my Italian followers, the equivalent: www.rivistaalata.it.

Yeah ok…so basically it’s a bunch of weird “ultra spiritual” orgies and squid games…got it

This doesn’t seem real.